Welcome back to Deep Dive, where I look at the full studio discographies and histories of some of the major names in progressive rock and progressive metal. It’s here that I highlight output beyond an act’s “classic” releases.

For those who don’t feel like reading this massive entry, I’ve included a TL;DR and ranking of albums at the end. I’m opting to explore albums chronologically, as opposed to a ranked-list format. The context in which albums were made is important, and this is an element often missed in a ranked-list.

Van der Graaf Generator (VdGG) were (and continue to be) a weird, weird band. Their classic lineup lacked guitars of any sort, but they managed to use organ and saxophone as cudgels to lay down nasty, proto-metallic music. Peter Hammill is one of the most distinctive vocalists in all of progressive rock; and paired with such unique instrumentation, VdGG managed to carve out a singular niche.

Hammill is also one of the few lyricists whose words I feel significantly added to his music. I’ve written at length about my general ambivalence to lyrics, but this band’s dark but often relatable imagery feels like an integral element of their identity.

Part I: Origins (1967-1969)

Van der Graaf Generator (an unintentional misspelling of “Van de Graaff Generator”) was formed in 1967 by a pair of students at University of Manchester: Chris Judge Smith (drums/wind instruments) and Peter Hammill (guitar/vocals). They soon recruited organist Nick Pearne and began playing heavy psychedelia in the vein of The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. Arthur Brown is one of the few decent comparisons for Peter Hammill’s vocal style. He’s weird as hell, often over-the-top, and dramatic to the extreme. But when he wants, Hammill can also summon beautiful, delicate sounds.

In 1968, the trio cut a demo and were offered a record contract by Mercury Records. (I could not find the demo anywhere online, but Chris Judge Smith said in an interview that it was mostly songs which would later appear on Peter Hammill’s solo album Fool’s Mate.) Not willing to quit college to try to make it in music, Pearne left the band. Hammill and Smith met classically-trained organist Hugh Banton upon arriving in London. Banton joined the group, and bassist Keith Ellis and drummer Guy Evans were soon added to the line-up, too.

In January 1969, VdGG released their debut single, “People You Were Going To” b/w “Firebrand” on Polydor Records. (The record labels will be important soon.) The A-side was quite different from the band’s later output, in that it was relatively musically light. But the dark lyrics foreshadowed their future direction more accurately. “Firebrand”, meanwhile, is more identifiably Van der Graaf-y, with its prominent organ and looming atmosphere. The demented vocals in the chorus of this song were provided by Smith. Not long after this single was released, though, Smith left the band, feeling superfluous.

This is where the band’s early history begins to get weird and confusing. VdGG had been signed to Mercury as the trio of Hammill, Smith, and Pearne; but they’d released their debut single on Polydor as the quintet of Hammill, Smith, Banton, Evans, and Ellis. Under pressure from Mercury, Polydor withdrew the single not long after its release. Hammill was now the only musician originally left on the Mercury contract, and Mercury refused to let the other musicians sign, so they were unable to record any more music.

In the meantime, Peter Hammill had been performing solo shows and began to record an album of his own material, enlisting Banton, Evans, and Ellis as studio musicians. The band’s manager struck a deal whereby Hammill’s solo record would be released as a Van der Graaf Generator album on Mercury, and the band would be released from their Mercury contract.

This first album, released September 1969, was The Aerosol Grey Machine. It’s a rough-around-the-edges, unpolished release. The seeds of Van der Graaf Generator’s sound had been planted, but they were unrefined. That roughness was not helped by the album’s muddy production. Unique among the band’s early releases, guitar featured prominently here.

The Aerosol Grey Machine opens with “Afterwards”, a pure slice of late-1960s psychedelic folk. Banton’s organ applies prominent wah-wah, and Hammill’s guitar twinkles over it all. It’s a good song, but it doesn’t do much to stand out from contemporary releases. This lack of distinctiveness is underscored on the two-part “Orthentian Street”. Had Peter Hammill’s voice been more generic, I could have easily mistaken this for a Traffic song.

“Running Back” meanders for nearly seven minutes in unimpressive acoustic mediocrity, as does the opening of the following “Into a Game”. The instrumental elements of this second song are more interesting, dynamic, and dark; and the closing minutes of “Into a Game” give the first glimpse of the distinctive Van der Graaf sound. Frenetic piano powers it along, with Hammill adding haunting vocal flourishes.

“Aguarian” is a good summary of the album. There are some very good ideas in this song, but in the end it’s somewhat unimpressive psych-pop that overstays its welcome. The following “Necromancer”, though, is the best song on the album. The piano is driving, and the bass is unusually forward. This instrumentation is paired with the strongest vocal melody on this release.

The Aerosol Grey Machine ends on “Octopus”, an early version of “Squid/Octopus” (more on that later). This is another instance of good ideas with unimpressive execution. Hammill’s palm-muted guitar line could have been something truly sinister if played by a more competent guitarist, but here it comes across more as awkward. (Even now, half a century later, Peter Hammill is still an unsteady guitarist.) Hugh Banton’s organ soloing is similarly weird-but-unimpressive, and this whole song feels like it needed to gestate a little more.

Not long after The Aerosol Grey Machine was recorded, bassist Keith Ellis left the band and was replaced by Nic Potter. Flutist Jeff Peach, who contributed to VdGG’s debut, was asked to join the band. Peach backed out after one rehearsal, though, as he felt his style did not fit well with the rest of the band. Saxophonist/flutist David Jackson would eventually join, bringing them to their classic lineup.

Part II: Initial Success & First Hiatus (1969-1972)

In late 1969, VdGG’s manager formed Charisma Records and signed the band as the label’s first act. They immediately set about recording their second album, The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other.

The Least We Can Do solidified Van der Graaf Generator’s signature sound, and the album cover itself featured a Van de Graaff generator on it. “Darkness (11/11)” opens the album on a grim note. Banton’s organ and Potter’s bass push Hammill’s vocals forward. The organ solo in the song’s midpoint demonstrated Banton’s willingness to work with sonic effects, and Jackson’s closing sax solo is a showcase for his distinctive style of playing two saxophones at once.

“Refugees” goes the complete opposite direction as the preceding song. After the grim pounding of “Darkness”, this is a sweet, gentle song where Hammill’s vocals are more traditional, and the lyrics are uncharacteristically hopeful. Banton’s organ is reminiscent of Procol Harum, and the inclusion of cello was a brilliant move. “White Hammer” opens with a sound palette similar to “Refugees”. The organ is docile, and Hammill sings cleanly. But this is a song about the Malleus Maleficarum and persecution of witchcraft in the Middle Ages, and the music does shift in tone to match the subject matter. The song’s last two minutes, in particular, are quite ominous. The organ has a thick layer of distortion, and Jackson’s saxes squeal and twist, fittingly evoking images of torture.

Side two starts with “Whatever Would Robert Have Said?”, referencing the then-recently-deceased Robert Van de Graaff. Electric guitar is a lead instrument on this cut, provided by bassist Nic Potter. It’s a weird song, and it often feels like it’s about to go completely off the rails, but the constant structural churn keeps the music moving forward. “Out of My Book” is a gentle little number that provides a nice, folky interlude.

The closing “After the Flood”, a song about cataclysmic floods triggered by a sudden inversion of Earth’s magnetic polarity, is pure gold. Hammill’s lyrics are fantastically grim, and his vocal tone matches. The chorus is huge and foreboding, and the ragged acoustic guitar, paired with Banton’s wall of organ, evokes mental images of the destructive waves described in the lyrics. Jazz influences are prominent on this track, as overdubs of flute and sax battle it out with one another in moments between the big vocal lines. As the song nears its outro, Peter Hammill quotes Albert Einstein discussing his worries over the Cold War arms race. The closing organ and guitar solos are powerful and majestic, with minor-key undercurrents reminding the listener of the song’s unhappy subject matter.

Only four months after The Least We Can Do was released, the band began recording their next album. Bassist Nic Potter quit the band partway through recording, and after a few attempts to replace him, organist Hugh Banton volunteered to play bass parts in the studio and to utilize the bass pedals of a Hammond organ in live settings.

The result of these sessions was H to He, Who Am the Only One. The H to He part of the title refers to the fusion of hydrogen to helium, and such scientific themes would be visited repeatedly on this album.

The first song, though, is about a shark. “Killer”, lyrically, is awfully straightforward for a Van der Graaf Generator composition; there’s not much metaphor here. In fact, this song was the result of the band taking bits of other songs and sticking them together to try to make something commercially successful. (The Least We Can Do received generally favorable reviews and cracked the UK’s Top 50, but major success always eluded the band, at least in the Anglosphere.)

The main riff of “Killer” is built equally around keys and sax, and Peter Hammill’s impassioned vocals lend a lot of weight to what could (potentially) be a pretty dumb song. Across the piece’s eight-plus minutes, the mood remains nervous and sinister, though one will notice the occasional flash of major-key brightness.

In contrast, the following “House with No Door” is a simple composition. A piano-based ballad, it was the last song recorded for this album, which makes the closing bass solo feel like something of a weird middle finger to Nic Potter. I don’t know if it was intended as such, but that’s how it feels to me.

“The Emperor in His War Room” is a fantastic song that mixes the band’s capacities for both understated anxiety and snarling bombast. Jackson’s flute is both delicate and piercing in turn, and the rest of the band also matches this oscillation. The blistering guitar solo in this song’s midsection is played by Robert Fripp of King Crimson. VdGG’s producer knew Fripp, and they wanted him to be the one to perform the solo.

Following the political drama of the preceding cut, “Lost”, thematically, is much smaller in scale. It’s a fairly simple song of lost love, but it’s a simple love song wrapped in a multi-layered, jazz-infused prog opus. Jittering jazzy flute and organ triplets kick things off, and Hammill’s plaintive tones add dramatic weight. Speedy instrumental moments which directly presage the modern micro-genre of brutal prog punctuate the spaces between the slow, melancholic verses. The climax is a swirling maelstrom of Hammill’s voice, heavily percussive piano chords, and rumbling saxophone.

H to He ends on its strangest song. “Pioneers over c” is a song about astronauts going through a black hole and experiencing time dilation. Rush explored this theme in “Cygnus X-1” in 1977, and Queen touched on it as well in “‘39” off 1975’s A Night at the Opera, but Van der Graaf Generator beat them both to the punch.

A woozy, airy organ and a quiet, pitter-pattering tom pattern open this song on a hypnotic note. After some tense, swelling organ chords, a jagged sax-and-bass-forward riff crops up, only to be supplanted by a lonely acoustic guitar. There are a lot of ideas in this song, and it was stitched together in the studio from many, many recordings, making it difficult to perform live. This wealth of ideas works in its favor at times, but it can also come off as disjointed and unfocused in other moments.

When H to He was reissued on CD in 2005, a pair of bonus tracks were included. One was an early demo of “The Emperor in His War Room”, but the other is a complete reworking of “Octopus” off their debut. Recorded during the sessions for their next album, this is a massive improvement over the song’s first iteration. It had been honed and developed in live settings, and now it was a 15-minute monster called “Squid 1/Squid 2/Octopus”. This is probably my favorite VdGG song, and it’s a pity it never got a proper release back in the day.

Acoustic guitar leads with a sense of yearning in the first minute of this piece. The relative warmth and hope of this section is soon ripped away as the band launches into a dark groove. Guy Evans’s drumming holds everything together as Banton’s organ and Jackson’s saxes battle it out against each other. After about five minutes of jamming, the band comes back together for the second verse. Hammill’s voice is more impassioned here, and there’s a growing sense of anxiety. The second instrumental passage is darker and more doom-laden than the first. Banton’s organ sounds like a hellish demon, and the saxophones squeal and twist, aided by various audio effects. As the song reaches its climax in the third verse, Hammill sounds demented, and the closing minute is downright apocalyptic.

Keeping to their rigorous recording schedule, it wasn’t long before Van der Graaf Generator began work on their next album. It was originally envisioned as a double-album in the vein of Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma. Disc one would be what was eventually released, whereas disc two would contain live-in-the-studio recordings of older songs and solo compositions by the individual members of the band. Considering such an ambitious venture to be financially unviable, their label axed the idea, giving us the single-disc album. Robert Fripp again provides electric guitar, but his parts are much less prominent here.

Pawn Hearts came less than a year after H to He and consists of three long songs. “Lemmings (Including Cog)” is classic VdGG from the get-go. It’s foreboding and unsettling. Hammill’s voice is delicate and powerful, and the instrumental elements are as brash as ever. In its midsection, the song shifts to an irregular, lurching rhythm. Saxophones honk and squawk, heavily-distorted organ dances downward, the drumming is both completely mad and incredibly deft. After briefly revisiting the opening theme, “Lemmings” ends on an extended organ drone, with quiet flutes and the gentle clattering of ride cymbals.

In contrast to the chaotic opener, “Man-Erg” features a beautiful piano as its lead instrument, and Hammill’s vocals are almost orthodox. There’s an uplifting, hopeful feel to this song’s first few minutes. Around three minutes in, the song takes a sharp turn. The distorted organ and piercing saxophones are oppressive, and Hammill shouts his lyrics like a madman. This was the first Van der Graaf Generator song I ever heard, and that one moment of the transition between the first and second parts of this song has been massively influential on both my tastes and my own songwriting style.

That evil-sounding passage is brief, though. For much of the song’s final five minutes, the tempo is relaxed, and there’s a tension between the hopefulness of the song’s opening and the pessimism of its second part. At the song’s close, themes from both those sections interpolate, underscoring the song’s themes of the conflict of light and dark within people.

Pawn Hearts ends with the longest song the band ever recorded. The 23-minute “A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers” is a singular achievement in the field of progressive rock, and it was the ultimate culmination of the sound of this era of the band.

Much like “Pioneers over c”, this suite was stitched together in the studio, and the band did not play it in its entirety in a live setting until 2013. (It was played piecemeal for a Belgian TV show in 1972 and then stitched together for broadcast.) It also features the band’s most experimental tendencies. They supposedly used every recording device in the studio for this piece, and Banton pushed beyond his usual piano and organ to play synthesizer and Mellotron on this track.

This suite opens with echoing electric piano, and Hammill’s voice is lightly processed. It sounds distant and lonely, underscoring the isolation of the titular lighthouse-keeper. Warm sax gently floats beneath the piano and vocal, creating a sense of wariness. This section dissolves in a moment of eerie drone, as saxophones bellow like ships in the distance, and a brief organ passage leads the track back to the opening theme.

Jackson’s saxophones underpin the next section. Hammill’s vocals and Banton’s distorted organs contrast against the reedy warmth. This passage, though, is followed by something quiet, understated, and lonely. It swells with bitterness and power before barreling forward into an off-kilter, tumbling instrumental passage where piano, organ, and synth wobble around each other in a disorienting manner.

The mellowest part of the suite follows. Sweet organ and delicate vocals provide a rare moment of optimism. It’s an introspective passage, and it adds wonderful diversity to this piece.

Afterward, though, is some of the darkest, most chaotic music the band ever recorded. Distorted vocals, walls of dense keyboards, and an unstoppable, bouncing rhythm combine to form an oppressive atmosphere. Banton’s use of the Mellotron was a brilliant move here; the swooping string effects complement the furious backing storm.

If you thought Rush’s “Fountain of Lamneth” had some hard cuts in it, just listen to the transition between part eight (“The Clot Thickens”) and part nine (“Land’s End (Shoreline)”). There was no elegant way to shift from the depression and angst to the gentle piano in the final part, so it’s just a hard stop.

There’s a sense of hopeful, upward movement, and the lyrics are ambiguous as to the lighthouse-keeper’s ultimate fate. “We Go Now” is a majestic and grand finale, and the closing organ solo is gorgeous.

When Pawn Hearts was reissued in 2005, a number of the songs recorded for the original double-disc vision of the album were included as bonus tracks. “Theme One” is a peppy instrumental written by George Martin (The Beatles’ producer, not the guy who still isn’t finished with The Winds of Winter. Come on, George, it’s been twelve years since the last book!) that was used as the theme music for BBC Radio 1. “W” is a solid, folky cut with a depressed but catchy chorus. A rerecorded (and in my view, inferior) version was released as a single in 1972. “Angle of Incidents” was written by drummer Guy Evans, and it’s a noisy, dissonant flurry of drums and saxophone that I can’t say I’m unhappy was cut from the record. Flute-and-sax player David Jackson’s “Ponker’s Theme” is a short, lounge-y jazz piece that also would have added nothing. “Diminutions”, from organist Hugh Banton, is an eerie, atmospheric piece that could be described as proto-drone. Overall, I’m very glad Pawn Hearts was cut down to one LP.

Though Pawn Hearts didn’t perform well in the UK, it was a massive success in Italy, topping that country’s charts for twelve weeks. VdGG toured Italy three times in the next year, and David Jackson complained he couldn’t walk down the street without being approached by fans. Such success wasn’t to last, however. The band was encountering financial difficulties, and their relentless touring and recording schedule was causing stress within the band. Needing a break, Peter Hammill left Van der Graaf Generator in mid-1972, effectively putting the band on ice.

The three remaining members teamed up with former VdGG bassist Nic Potter and other musicians to release an instrumental record. Both the band and the album were called The Long Hello. It’s fine. It’s perfectly decent, jazzy prog, but it’s really nothing special.

In between Pawn Hearts and the band’s eventual reunion, Peter Hammill put out five solo records, all of which are great, and all of which feature members of Van der Graaf Generator. However, there is a definite difference between these records and the band’s output. Hammill has stated on multiple occasions that though he is the primary songwriter for Van der Graaf Generator, how the songs are arranged is a democratic, band-wide affair.

I was once asked if I’d do a Peter Hammill Deep Dive at some point in the future, and that was a pretty easy no. While I have heard and really like his first five records, the man has a staggering thirty-six solo albums to his name. I had to listen to a few albums for the first time for this article, but it was a manageable number. Four or five. I don’t want to have to plow through two-and-a-half dozen records that I don’t already have some degree of familiarity with for one of these columns.

But, considering the timing of these albums, I’ll give a brief overview of them. They won’t be included in the ranking at the end.

Fool’s Mate was released a few months before Pawn Hearts. The best way I can describe it is “happy Van der Graaf Generator.” It’s sunny and peppy and a lot of fun. I especially love the opening “Imperial Zeppelin”. 1973’s Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night is more stripped-back, minimal, and folk-influenced. The exception is the dark, powerful “(In the) Black Room/The Tower”. This sounds like classic Van der Graaf, and the band has occasionally performed it live. The Silent Corner and the Empty Stage followed in early 1974 and is broadly similar to Chameleon – it even has a long, Van der Graaf-y closing track. Only five months later, he put out In Camera. This release has more muscle to it than his previous two albums, though folk elements are still prominent. “Gog” has been a staple of the band’s live sets, and “Magog” is sinister musique concrète. Meanwhile, 1975’s Nadir’s Big Chance is gritty and guitar-centric, with flavors of garage rock and proto-punk.

Part III: First Reunion (1975-1978)

After a few years away from the band, Hammill, Jackson, Banton, and Evans felt like they were in a good enough place to get back to recording together full-time. They immediately resumed at their former breakneck pace, recording three albums in a twelve-month span.

Released in late 1975, Godbluff sees a distinct shift in the band’s sound. A Hohner clavinet is used prominently on all four songs on the album, and Hammill plays electric guitar on the record. (Previous instances of electric guitar had (mostly) been played by either former bassist Nic Potter or King Crimson bandleader Robert Fripp.) There’s an anxious, edgy feel to Godbluff, and it suits the band very well.

Gentle flute and whispered vocals start the album off on an unassuming note on “The Undercover Man”. It swells gradually, and the relatively stripped-down arrangement allows room for the individual members of the band to shine through.

“Scorched Earth” sees the band return to some familiar modal territory. Where the opening track had been relatively upbeat, this piece is dark, and the clavinet adds a unique crunch to everything. The song’s instrumental midsection sees some great interplay between Jackson’s saxes and both organ and clavinet. The urgency keeps building throughout the nearly-10-minute runtime, and it eventually reaches an explosive climax.

Skittering drums gradually fade in for the introduction of “Arrow” alongside some bass noodling and the errant squeal of saxophone. After gently meandering for a few minutes, Hammill’s voice barges in and demands attention. The backing track remains stripped-back, and the chorus features a haunting, foreboding build-up. Jackson’s saxophones snarl menacingly in the instrumental middle. As “Arrow” builds toward its peak, Hammill’s vocal performance is especially arresting, even by the standards of someone as theatrical as himself.

Godbluff closes on its longest cut, “The Sleepwalkers”. An odd organ-and-sax pattern driven along by a marching drumbeat opens things at the start. Evans’s use of woodblocks in his drumming add a distinctive character to this track. Wonky jazz and Latin flavors crop up at moments, giving those passages a hazy, dreamlike quality. The song’s middle few minutes are instrumental and feature an organ solo which is pretty distinctive in Banton’s history, though it is awfully low in the mix (the clavinet buries it). This section is followed by one of Jackson’s best solos, though. It’s a hard-rocking, melodic passage, and Hammill’s electric guitar flourishes add a lot of depth. This all resolves wonderfully into the closing verse.

Only six months later, the band released Still Life. “Pilgrims” kicks off with gentle, almost Canterbury-sounding organ. Hammill’s vocals are delicate, and there’s a jazzy character to the rhythm. It swells and recedes nicely; this is one of the band’s more straightforward songs from their classic era.

Next comes the album’s title track. The opening is understated, much like the preceding cut. It takes a few minutes to get going, but eventually Banton’s organ gains some crunch, and Jackson’s saxes add some staccato punch. In contrast to its impactful middle section, “Still Life” ends on a minimal voice-and-piano passage.

“La Rossa” jumps into things more quickly, and I get echoes of both “Lemmings” and “The Sleepwalkers” from this piece. This opening passage is loud and maximal, and I like how forward the bass is. Moving into the song’s middle, things slow down, but there’s still a sense of menace and darkness to it. Despite this song’s length, it feels like one coherent, evolving piece, as opposed to some multi-part suite.

Side two opens with the smooth, sentimental saxophone of “My Room (Waiting for Wonderland)”. This song’s first passage is unhurried, and even when the band switches things up in its second half, they keep the tempo on the slower end of things. The arrangement is simple and allows the individual instruments room to breathe, as opposed to some of the smothering organ-and-sax passages on Still Life’s first side.

Closing things out is “Childlike Faith in Childhood’s End”, one of my favorite VdGG songs. The opening flute arrangement is fittingly sweet for the title, and anxious currents soon cut their way through the song. As things move along, the urgency increases, and Banton’s organ swirls commandingly. Hammill’s voice is as powerful as ever here, and his lyrics really enhance things. In the second half, weird jazz flavors affect the instrumentals, particularly Jackson’s saxophones. The conclusion is huge and important-sounding; it’s an exceptionally strong climax.

Only six months after Still Life, the band put out their next album, World Record. “When She Comes” opens with light and jazzy drums and weird flutes flitting about. Hammill’s guitar is more prominent here (and throughout the album as a whole), and it adds some nice textural contrast. Despite some good compositional ideas, the vocal melody feels awkward, and this eight-minute song probably could have been trimmed down a bit.

“A Place to Survive” features some of the same melodic awkwardness as the preceding song, and that’s an issue that runs through a lot of World Record. The songs on the whole are still pretty enjoyable, but a lot of this album just feels like a step down from their previous output. I can’t quite put my finger on what it is exactly, though. Despite being ten minutes long, I don’t have much to say about this song. I do like Jackson’s saxophone arrangements, Banton deploys some fun tones on his organ, and it ends on a strong note.

“Masks” kicks things off with gentle, flowing saxophone and soulful organ. This slow-moving cut is probably my favorite song on the album, and it features some of Hammill’s best use of guitar. Slow, distorted chords add some nice grit. In the song’s second half, things pick up, and Hammill’s guitar playing is noticeably shakier. It still works quite well, though.

Side two opens with the twenty-minute “Meurglys III (The Songwriters’ Guild)”. Meurglys is the name of one of Hammill’s guitars, with that name being derived from a 12th Century French poem. It’s the name of a sword belonging to Ganelon, a knight who betrays Charlemagne in the story. That’s a very prog-rock way of going about naming your guitar.

Unusual name aside, this is definitely my least favorite of Van der Graaf’s longer pieces. That’s not to say it doesn’t have its moments. The main riff to the verse is classic Van der Graaf Generator. The quiet passages are effective and play to Hammill’s strengths as a vocalist. The heavy passage around the song’s midpoint is an exceptional moment as well.

However, this song’s main drawback is its interminable length. It probably could have been halved without losing a lot of the effect. Much of this song is instrumental, and it prominently features Peter Hammill’s eponymous guitar. He’s a decent, idiosyncratic rhythm player, but he’s not a particularly strong soloist. He reminds me a lot of Omar Rodriguez-Lopez, if Omar slowed things down. His guitar always sounds slightly out-of-tune, and his attempts to be flashy are usually unsteady.

The most egregious sin of “Meurglys III” is its seven-minute reggae-influenced jam session at the end. This all could have been lopped off, as it’s all just Hammill soloing over Banton’s bouncing organ, with the occasional honk from Jackson.

World Record ends on a good song, though. “Wondering” is a sweet, quiet piece for much of its runtime, and Jackson’s flutes and Banton’s organ give this song a hopeful, victorious feel.

Following the tour in support of World Record, Hugh Banton left the band, due primarily to some financial difficulties. Jackson left the band shortly thereafter, too, though he does appear on two songs on their next album. Hammill and Evans then brought former bassist Nic Potter back to the band, while also adding violinist Graham Smith.

For the band’s next release, 1977’s The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Dome, they shortened their name by dropping the word “Generator”. The songs are also shorter and much more guitar-centric.

“Lizard Play” features an off-kilter rhythm and some folky guitar work. The vocal arrangements are unusual, and Smith’s violin squeals and squeaks in ways that complement the folk elements of the song. “The Habit of the Broken Heart” is more laid-back than the opener, and it features some great bass work from Potter. By the song’s end, it’s evolved into something quite peppy and fun.

Quiet piano opens “The Siren Song”. It’s a very nice ballad, and Smith’s violin is a seamless replacement for Jackson’s saxophones and flutes. I also love the rubbery, wobbly effect Potter uses here. Around the midpoint, the mood shifts suddenly into something more upbeat, and Smith’s violin begs comparison to Electric Light Orchestra’s early, string-centric sound.

“Last Frame” takes its time to get going. It’s languid and emotional, and the instrumental elements mesh nicely. There’s an art-punk flair to the guitar work as the song progresses, and Potter’s bass has a lovely bit of fuzz to it.

Side two starts off with “The Wave”. It’s another gentle ballad, but the instrumental is strong enough to carry it. I’m normally not big on balladry, but the ones on this album are all well-composed.

“Cat’s Eye/Yellow Fever (Running)” is one of the harder-rocking cuts on the record. It’s jittery and anxious, and Smith’s violin evokes a tense atmosphere. He plays an edgy pattern for much of the song, which calls to mind the iconic string stabs of the film Psycho. Its second half consists largely of many layers of overdubbed violin.

David Jackson provides saxophone on “The Sphinx in the Face”. Between the spare, funky instrumental and Hammill’s oddball vocal style, it’s easy to draw comparisons between this song and early Talking Heads output. This song displays some of the densest composition on the whole album, and those passages bear the most in common with Van der Graaf’s classic sound.

The last (proper) song on the album is “Chemical World”. It can feel a bit disjointed at moments, but it still has its strong elements. As with much of the record, Smith’s violin really stands out as the star. Flowing out of this closer is a brief reprise of “The Sphinx in the Face”.

The 2005 remaster features a few bonus tracks. One is just a demo of “The Wave”, but the other two are unique songs. “Door”, though appearing on a live recording, never saw studio release. It’s crunchy, weird, and plodding, but I wouldn’t call it essential. The other bonus track, “Ship of Fools” was a France-exclusive B-side of “Cat’s Eye”. It’s a morose, piano-and-violin led instrumental, but it doesn’t stand out.

Cellist/keyboardist Charles Dickie joined the band for the tour in support of The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Dome, and this line-up recorded the live album Vital. (Jackson was also present for part of the tour, appearing on roughly half of Vital.) It isn’t typical Van der Graaf Generator, but it’s still a really great release. It’s gritty, powerful, and punky.

However, the band encountered financial difficulties shortly thereafter, and they disbanded before Vital even hit the record store shelves.

In 1982, a collection of outtakes and rehearsal recordings, titled Time Vaults, was released. Initially put out only on cassette for their fan club, these tracks were recorded by the band’s classic lineup during their 1972-75 hiatus. However, the audio quality is not very good. These were demos, so the mastering is rough. Nonetheless, there is some worthwhile music here.

This collection opens with “The Liquidator”. Piano and saxophone echo in its introduction, and Evans’s drumming is strong. The melody is rather light and psychedelic. It reminds me of latter-era Beatles or classic ELO, albeit with dashes of Van der Graaf-y weirdness here and there. It’s uncharacteristically light and catchy, and it is a strong song overall.

Following is “Rift Valley”. I can’t speak quite as highly of this cut. Hammill’s guitar is the lead instrument here, and it’s often of questionable quality. The melody is awkward and feels half-formed. Organist Hugh Banton is either not present, or his organ is far too quiet, leading to this cut sounding quite thin. There is a dark, descending guitar riff that sounds like classic VdGG, however.

“Tarzan” is a weird, funky little instrumental. While fun, it’s clear why this never made it onto a studio record. “Coil Night”, while less silly, is in the same vein as “Tarzan”. It’s fine, but it’s also clear why this was left on the cutting room floor.

The title track comes next, and it’s a collage of several snippets intercut with studio chatter. It’s absolutely skippable.

“Drift (I Hope It Won’t)” has especially poor audio quality, and it features some warm organ alongside powerful drumming. “Roncevaux” suffers from similar sonic quality issues, but it shows a lot of promise. It’s a storming, heavy cut, and I would’ve loved to have heard a properly-recorded version of this piece.

The next song is listed both as “It All Went Red” and “It All Went Up” on different releases, though the “Red” version appears to be official. It’s moody and eerie, like a heavier version of Pink Floyd c. 1969. Sadly, it’s also muddy and unclear. “Faint and Forsaken” is a swirling, short instrumental where Banton’s organ tones shine, even with the terrible audio quality.

Time Vaults ends on an early version of Peter Hammill’s “Black Room”. Despite it being a strong underlying composition, this song sounds the worst of any on the album. This one is right down there with the rawest, kvltest, recorded-in-a-basement-on-a-tin-can-est black metal I’ve heard, with regard to poor audio quality.

If you’re a fan of the band, Time Vaults is absolutely worth your time. There are a lot of strong musical ideas here. It’s just a pity they couldn’t have been recorded with greater fidelity.

Part IV: Second Reunion (2005-Present)

After the band’s 1978 breakup, the members of the classic lineup kept in touch and regularly collaborated with one another. They performed together on occasion throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, and they decided to re-form as the classic quartet in 2004.

The resulting album was 2005’s Present. In some ways, it bears resemblance to the band’s original plans for Pawn Hearts. Disc one consists of group compositions, and disc two is largely improvisational.

Disc one opens with “Every Bloody Emperor”. It’s a solemn, trudging piece that gradually builds in gravity. Hammill’s voice is still strong, and I like some of the odd keyboard tones in this song’s second half. However, this track doesn’t quite land with me. It feels like it’s lacking a bit of the Van der Graaf Generator spirit.

The instrumental “Boleas Panic” follows, and it features a smoky atmosphere led by Jackson’s saxophone. Though the pace is much slower than a lot of their classic work, this is more in line with what I expect of the band. Banton’s organ glimmers in support, and Evans’s drumming is understated but effective.

“Nutter Alert” has an impactful opening featuring an odd, crunchy electric piano tone, biting sax, and slightly-distorted vocals. It’s enthralling and insistent. This is one of their absolute-best tracks of the 21st Century.

Sharp electric guitar opens “Abandon Ship!” with an irregular pattern. Banton’s organ is a bit clean and jazzy for this context, but the song’s overall oddness suits the band well. This cut evolves well and winds up being pretty solid.

Another herky-jerky riff kicks off “In Babelsberg”. There are some good ideas here, and it’s unmistakably a VdGG track. Unfortunately, Hammill’s guitar tone is atrocious, and it is mixed far too loudly.

Disc one of Present ends with “On the Beach”. It opens with a bit of studio chatter and electric piano, but it soon becomes a straightforward ballad. From its simple vocals-and-piano intro, the song slowly adds a bit of pep. Jackson’s saxophone is especially jazzy here, and Evans’s drumming is tactful. Baton, meanwhile, lays down a warm, smooth bassline. Hammill has some fun with the vocal arrangements in the second half, as well. Despite an underwhelming opening, this winds up quite the enjoyable, laid-back song.

Moving onto the improvised disc of Present, “Vulcan Meld” fades in slowly. Saxophone is the lead instrument here. Multiple layers of sax are overdubbed on top of one another, and they’re often laden with audio effects. It eventually turns into a growling, sinister, keyboard-driven piece. However–and this will be a refrain for disc two–this goes on for too long. There are good ideas, I’m sure it’d be fun to hear in a live context, and they probably could have workshopped a number of motifs into proper songs; but seven minutes of improvised instrumental music easily gets exhausting.

“Double Bass” features some cool synthesizer experiments uncharacteristic of the band, and overall it’s more focused than the opener. (It’s still two minutes too long, though.) “Slo Moves” is torpid and moody, but it doesn’t say or do much. It wouldn’t be bad on a soundtrack for something, though.

“Architectural Hair” has a promising beginning. It’s the band’s usual dark sound with guitar, organ, and sax. Despite this being the longest track on the record, it doesn’t feel overlong. (Well, maybe a little, but less so than the preceding pieces.)

I always start to lose interest around this point on the disc, due in large part to how meandering many of these songs are, so forgive me for the ensuing brevity. “Spanner” is woozy and dissonant, and “Crux” is the sweetest of these improvised tracks. “Manuelle” gives me flashbacks to “Meurglys III” and its reggae flavors, though this is more interesting than that jam session. “‘Eavy Mate” is the shortest of these songs, at a hair under four minutes, but it’s one of the weaker moments. “Homage to Teo” is relatively warm and quite jazzy, and the closing “The Price of Admission” bears some similarity to Magma.

The second disc of Present has a lot of good ideas, but it’s entirely too long. Coupled with a really solid first disc, Present is a strong addition to Van der Graaf Generator’s discography.

Following the tour for Present, David Jackson left the group, and VdGG decided to push on as a trio.

The band’s first release as a trio was 2008’s Trisector. Songs on this release are (mostly) terser than their prior output, but considering some of the bloat on Present, that’s a good thing. “The Hurlyburly” fades in slowly with a twangy guitar line, but it’s got a really fun groove once it gets going. Hammill’s guitar playing still isn’t great, but it’s more competent than elsewhere on this album. Despite this being a decent track overall, the loss of Jackson really stripped the band of a lot of their distinctiveness. The fact that this track is an instrumental only seems to exacerbate its genericness.

A somewhat Baroque organ-and-piano pattern opens “Interference Patterns”. Hammill’s voice goes a long way in defining the Van der Graaf sound. The melody is the band’s signature minor-key weirdness, and his theatricality is greatly appreciated. “The Final Reel”, meanwhile, is a slow-moving piece with subtle jazz touches. It reminds me a lot of David Gilmour-era Pink Floyd ballads (including being two minutes too long).

“Lifetime” tries to be moody, but it’s more boring than anything else. “Drop Dead”, in contrast, is a hard-rocking piece with a somewhat-awkward bluesy riff. “Only a Whisper” plays with dynamics a bit but remains mostly quiet throughout its runtime.

“All That Before” is one of the best cuts on the album. Hammill’s guitar and Banton’s organ have great synergy, and the vocal melody is memorable. The lyrics are pretty fun, too.

At twelve-and-a-half minutes, “Over the Hill” is nearly twice as long as the next-longest song on Trisector. The slow, organ-led intro reminds me of material off of Still Life. Instrumental passages feature interplay between organ and piano with oddball riffs and unusual chords. In the song’s second half, Banton’s organ gives this cut a swelling, triumphant atmosphere. During the climax, Hammill’s guitar evokes Jackson’s saxophone style marvelously.

Trisector ends strong. “(We Are) Not Here” features an eerie, ominous organ line, and Evans’s percussion has a difficult-to-describe rhythmic oddness. The vocal performance is also classic Hammill. It’s emotive, idiosyncratic, and over-the-top, featuring both his uniqueness and his ability to sing in conventionally “pretty” ways.

A Grounding in Numbers followed in 2011. I actually had an opportunity to see them on tour for this release while I was in Europe. However, I was way too jetlagged to do anything and was compelled to skip the show. I regret not seeing them (as I doubt they’ll ever tour North America, especially the west coast), but I was far too tired to attend a concert that night.

“Your Time Starts Now” is a slow-moving, swelling, and ultimately forgettable track. Hammill’s vocal arrangements are strong, and it’s another good lyrical outing, but there’s nothing that distinctive about this song. “Mathematics” is another clever lyrical piece, but the music stays in a middling, piano-jazz lane.

“Highly Strung” switches things up a bit with a fittingly anxious guitar line. There are weird new-wave and art-punk influences. I’m still not crazy about Hammill’s guitar style, but the strange edginess of this cut suits the band well.

“Red Baron” is a short, atmospheric instrumental that sounds like it was originally recorded for disc two of Pawn Hearts, but at barely two minutes, it doesn’t overstay its welcome.

“Bunshō” is a pretty strong cut. Organ and guitar meld into a moody backdrop for Hammill’s voice. There’s a sense of drama to this song, and the development is well-plotted. In the song’s final couple minutes, the band does a great job of playing their signature dark and jagged prog.

The instrumental elements of “Snake Oil” are strong, but the vocal melody feels somewhat forced. That piece is followed by another short and disorienting instrumental, “Splink”.

“Embarrassing Kid” has an awkward and uneven riff, but that was probably intentional given the song’s title and subject matter. In contrast, “Medusa” is mournful and gloomy. The arrangement is minimal, and the song’s brevity works in its favor. It works as an interlude, but it would have been a dull piece had it been dragged out to five minutes, like many other latter-era VdGG songs.

“Mr. Sands” is an example of one of those too-long songs. The ideas in it are good, but it would have worked fine as a sub-four-minute piece. “Smoke”, another short song, follows, and it’s one of my favorites on the album. It has a fun, loose, wobbly feel; the band has always excelled when they’ve leaned into weird ideas. “5533” has an even looser, more shambolic atmosphere. The guitar (at least some of which is played by drummer Guy Evans) is especially weird. It’s skittery, jumpy, and heavily affected.

A Grounding in Numbers ends with the harpsichord-heavy “All Over the Place”. This is one of the better songs on the album, and it’s well-constructed. However, it still suffers from some of the same ills seen elsewhere: it’s a bit too long, and it feels like it could have used a little more refinement.

Only a year later, Van der Graaf Generator put out ALT, an instrumental album. While the band is no stranger to instrumentals, in my mind, Peter Hammill’s voice is the most defining characteristic of the band. Yes, David Jackson leaving did rob the band of some of their character, but the strongest moments on Trisector and Grounding proved the band can soldier on saxophone-less. Wordless, though?

“Earlybird” is a dull blend of tabla and bird calls that does nothing for four minutes. “Extractus” is a hazy, percussion-forward piece, and “Sackbutt” continues in that same vein.

“Colossus” maintains a sparse atmosphere that reminds me of the band’s instrumental experiments intended for disc two of Pawn Hearts, and at six-and-a-half minutes, it is entirely too long. “Batty Loop” is another percussion-forward interlude that does nothing interesting.

“Splendid” has some better ideas than preceding cuts, but it’s still unfocused, poorly-produced, and quite weak compared to most of their prior output. “Repeat after Me” has a bit more structure and prominently features some very pretty piano. That said, this song is about four minutes too long.

Weird synthesizer bloops and light jazzy elements make up “Elsewhere”. “Here’s One I Made Earlier” is an uninteresting drone piece. “Midnite or So” feels like an actual composition, but it doesn’t do much to stand out. Evans’s percussion is mixed far too loudly, especially near the end. “D’accord” is more dull drone. “Mackerel Ate Them” has some chaotic drumming and bizarre guitar, though it doesn’t amount to anything.

A hint of structure shows up again in “Tuesday, the Riff”. This one feels like something the band could have refined into something really good, but instead it was wasted on this underwhelming instrumental.

ALT ends on the nearly-11-minute “Dronus”. You can probably guess what this is like, as well as my thoughts on it.

ALT is far and away this band’s worst album. It feels like a substantially weaker version of disc two of Present. Composition is minimal, and the production is awful. There are very few points where the band is recognizably themselves.

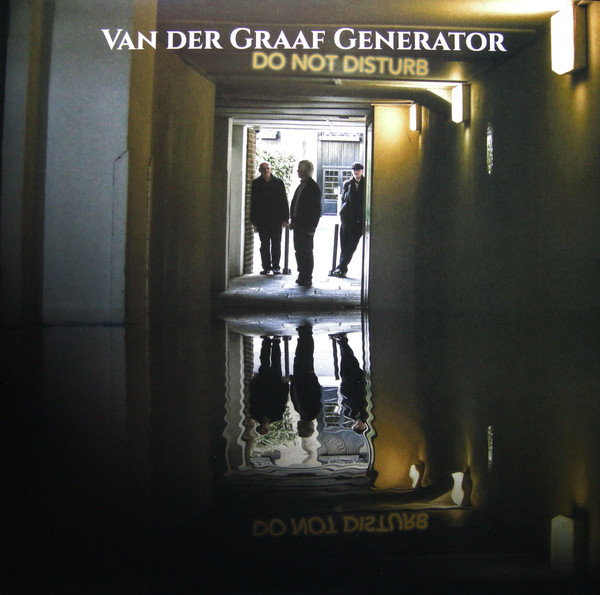

Van der Graaf Generator returned in 2016 with Do Not Disturb. I’ve read some mixed messages online about whether or not this is officially the band’s last album or not, but it has a sense of finality to it. The band is still together, and they’re still touring, but they may not be recording anything new anymore. (Hammill, though, is still pumping out solo records.)

Do Not Disturb opens on the gentle, nearly-Floydian guitar of “Aloft”. This calls to mind some of Pink Floyd’s more pastoral moments, like “Fat Old Sun” or “Fearless”. But Hammill’s voice is unmistakable. When Banton’s organ comes in, it’s a classic Van der Graaf line. The melody is dark and distinctive, though I’m not crazy about the inclusion of the melodica(?). This track runs a bit long, but the underlying composition is strong enough to forgive the extended runtime.

“Alfa Berlina” starts with some strange vocal effects and ambient traffic noises. As the verse gets going, it’s a simple arrangement of Hammill’s voice over a basic backing of organ and drums. It’s a bit bland, but not bad. “Room 1210” is piano-based and keeps a similar, slow pace to start. It eventually shifts to a more distinctively-Van der Graaf riff, and continues to move back and forth between this section and the prior piano passage for the rest of its runtime.

“Forever Falling” sounds almost like a Dire Straits song at first. The particular guitar and organ tones are quite Knopflerian. Harsh, dissonant passages cast that comparison aside quickly enough though, and jittering instrumental antics make the track feel much more distinct.

Following the brief, airy instrumental “Shikata Na Gai”, “(Oh No I Must Have Said) Yes” kicks off with a tumbling distorted guitar riff. Hammill’s guitar suffers from its usual lackluster tone, but the underlying passage is decent. There’s a quirky, early-Devo-like quality to parts of this track, balanced against the more trudging main theme. The song’s midsection is much quieter and features some drawn-out guitar noodling before closing out on a reprise of the main riff.

The first half of “Brought to Book” is a somewhat dull, jazzy piano piece. As organ and guitar enter in the second half, it improves somewhat, but it remains generally unimpressive. “Almost the Words” is almost the same as the preceding cut, though I like it more.

Do Not Disturb ends with “Go”. A somber organ is the main focus of this piece. There’s a sense of gravity here, and though it doesn’t stand out in isolation, it’s a fitting way to end their career, if indeed that was their intention.

Part V: TL;DR and Ranking

Van der Graaf Generator was one of the most distinctive bands of the first wave of progressive rock. Their dark, organ-and-sax-led glory years saw them put out a string of fantastic albums, and even their 21st century output, sans David Jackson, has mostly been pretty decent.

- Pawn Hearts (1971) – 100/100

- H to He, Who Am the Only One (1970) – 94/100

- The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other (1970) – 92/100

- Godbluff (1975) – 91/100

- Still Life (1976) – 88/100

- The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Dome (1977) – 84/100

- Trisector (2008) – 78/100

- Present (2005) – 75/100

- World Record (1976) – 72/100

- Do Not Disturb (2016) – 70/100

- Time Vaults (1982) – 70/100

- The Aerosol Grey Machine (1969) – 66/100

- A Grounding in Numbers (2011) – 63/100

- ALT (2012) – 38/100

This is a FANTASTIC overview of one of the best bands ever. THANKS!

LikeLike