Hamtaï! Welcome back to Deep Dive, my series where I explore the extended studio discographies of the giants of progressive rock and metal. I’ve got a weird one for you today: Magma, the founders of zeuhl.

For those who don’t feel like reading massive entries in their entirety, I’ve included a TL;DR and ranking of albums at the end of this piece. I’m opting to explore albums chronologically, as opposed to a ranked-list format. The context in which albums were made is important, and this contextual element is often overlooked in many ranked-lists.

Magma has always been a weird band. I’ll delve into what exactly zeuhl is below, but even beyond the structural strangeness of their music, the band’s composition has varied wildly over the years. At the time of writing, Wikipedia lists 12 current members and 22 former members; and Rate Your Music names 11 current members with a staggering 89 former members. Much of this can be attributed to their frequent shifts in sound, ranging from their very wind instrument-heavy first albums, to mid-career funk experiments, to later albums which prominently featured vibraphone. Multiple vocalists have always been a signature element of their sound as well.

Magma has been incredibly consistent across their career, in terms of the quality of their work. Even their worst album isn’t all that bad. I’ll also give a quick shout-out to their live performances. I saw Magma on their 2016 US tour, and that was one of the absolute best live shows I’ve ever seen, only seriously challenged by my experiences seeing Rush and Moonsorrow. This column only covers studio output in any depth, but the live albums Hhaï and Retrospektïẁ (I-III) are some of their best work. I’m a big enough fan that I personally own the 12-disc live box set Köhnzert Zünd.

Before we get going, though, I’m sure those of you unfamiliar with Magma are asking…

Mëkanïk 0: What the Hell Is Zeuhl?

Zeuhl is among the strangest of progressive rock’s subgenres, and it is one of the few musical movements to be able to trace its origin definitively to one act. Most of Magma’s music is sung in the invented language Kobaïan, designed by drummer, composer, and occasional vocalist and pianist Christian Vander. The word “zeuhl” itself means “celestial” or “celestial music” in Kobaïan, and it certainly lives up to its name. This variety of prog heavily features chants, copious amounts of jazz, avant-garde flavors, martial drum beats, and matra-like repetition.

As someone with a passion for constructing languages, I’d argue it’s fairly generous to call Kobaïan a language. It’s more than just the gibberish of Sigur Rós’s “Hopelandic,” but it definitely falls short of functional conlangs like Quenya, Na’vi, or Esperanto. Words do have meanings, and (incomplete) Kobaïan glossaries can be found online, but Kobaïan grammar seems fuzzy-to-nonexistent. On a scale of zero (scat singing) to ten (Klingon), I’d put Kobaïan around two or three.

Christian Vander has been quite open about how Kobaïan is based more on general feelings than prescriptivist grammar. Yes, there are set words, but the ultimate goal of Kobaïan is to enhance the music. In that way, it is perhaps semi-analogous to the semi-English of “Jabberwocky”.

Much of the lexicon is derived from (faux-)Germanic and Slavic, but the pronunciation is filtered through the band members’ native French. So, “zeuhl” is pronounced something like “dzӧl.” Some sources say the pronunciation should be closer to “tsoil,” following German spelling and pronunciation rules, but I’ve never heard the band members pronounce it like that. As far as I can tell, the proliferation of diaereses over vowels has no bearing on how they’re pronounced by the band members.

Zeuhl, for its first two decades or so, was an exclusively French phenomenon. Bands like Eskaton, Rialzu, Shub-Niggurath, and Dün all took inspiration from Magma’s strangeness by blending astral prog, jazz, and avant-garde influences. Starting in the 1980s and 1990s, though, a handful of Japanese acts began playing their own brand of zeuhl, most notably Ruins, Koenji Hyakkei, Happy Family, and Bondage Fruit. Building off the style pioneered by Magma, these acts were often more frenetic and incorporated elements of math rock.

Since the new millennium, zeuhl has remained a niche genre, but it has expanded beyond its traditional strongholds of France and Japan. To give a few examples, there are Guapo (UK), Pinkish Black (USA), Dai Kaht (Finland), and Papangu (Brazil).

Many subsequent zeuhl bands have followed in Magma’s footsteps by choosing to deploy nonsense vocals, such as Ruins, Koenji Hyakkei, Dai Kaht, Corima, and VAK. (Dai Kaht and Corima are especially interesting to me. The former band has certain cross-linguistically-uncommon diphthongs indicative of their native Finnish, while the latter has influences from Spanish and Nahuatl.) Many bands have sung in their native tongues, though, like Eskaton (French), Ga’an (English), and Papangu (Portuguese), and yet others are more strictly instrumental (ni, Guapo).

Mëkanïk I: Early Years (1965-1971)

Magma is the first subject of a Deep Dive originating from a country outside the Anglosphere, and I am not a Francophone. As such, information can, at times, be spotty. I have relied on Google Translate renditions of the French Wikipedia articles on the band and its members to fill in gaps in biographical information.

Magma is the brainchild of Christian Vander (né Vanderschueren), the band’s drummer and primary songwriter. He is the adoptive child of French jazz musician Maurice Vander (also né Vanderschueren), so he was exposed to jazz and experimental music from a young age. He has specifically cited John Coltrane and composers Carl Orff and Igor Stravinsky as major influences.

Prior to forming Magma, Vander played in the short-lived rock & roll band, Wurdalaks (named after a vampiric demon of Slavic origin), whose recordings have since been lost. After that, he joined a band called Chinese, about which there is no information beyond the fact that it briefly existed and quickly changed its name to Cruciférius Lobonz.

Vander was deeply affected by the death of John Coltrane in 1967, prompting him to go to Italy and play jazz in clubs across the country for two years. Vander returned to France in 1969, where he met bassist Laurent Thibault and saxophonist Rene Garber. After recruiting vocalist Lucien “Zabu” Zabuski and organist Francis Moze, the five founded the band Uniweria Zekt Magma Composedra Arguezdra, or Magma, for short.

Before the band even recorded their first album, there was significant instability within this lineup. Zabu would be replaced by Klaus Blasquiz (who would be with Magma until 1980), and additional musicians continuously cycled in and out, including the addition of a full brass section. This sort of volatility would be a regular occurrence in Magma’s first incarnation, so I won’t cover lineup changes in great detail. I will mention when long-running band members join or leave, though.

Magma released their self-titled debut album (retitled to Kobaïa upon its reissue in the 1980s) in late 1970, and it was quite a statement. It’s a massive, sprawling double album that clocks in at over 80 minutes. It’s a bit more conventional and easily digestible than the stuff Magma would eventually produce, but the band’s sound was already quite established, even at this early point in time.

As far as I am aware, all of Magma’s albums (minus one) are lyrically and thematically linked, and each album constitutes a new chapter in the mythos of Kobaïa. Notably, the albums do not tell the overarching story in chronological order. For example, 2004’s K.A. is the earliest part of the story. Considering my assessment of Kobaïan as “not really a language” above, I have heavily relied on blogs, forum posts, and one particularly helpful magazine article to piece together the content of the narrative. Even with all this outside help though, the plot often remains fuzzy and vague. I’ve included my best estimation of the storyline progression at the end of this article.

Magma tells the story of humans fleeing a doomed Earth to settle the planet Kobaïa. (Fun fact, there is a village in Sierra Leone called Kobaia!) The lyrics are mostly in Kobaïan, but there is some English on Magma.

Magma’s first disc tells the story of humans fleeing Earth for Kobaïa and establishing a new, harmonious society. The first song, “Kobaïa”, begins with a jazzy blues groove that’s almost orthodox. The lyrics are sung in English in this first part and tell how humans had to flee an apocalypse. The brass section honks and trills, adding to the tension of the piece. The song’s midsection features many long, slow, drawn-out notes paired against occasional cacophonous bursts of energy.

“Aïna” follows and starts as a gentle, jazzy piece led by piano and woodwinds. By its midpoint though, the song has become more urgent, and that upward trajectory continues until its conclusion. “Malaria” continues with the tense atmosphere of the preceding tracks, and there is some lovely flute mixed in with other odd passages.

Side two kicks off with the gentle flutes of “Sohïa”, which at times are evocative of King Crimson’s more idyllic output. A crunchy, propulsive guitar line and reeds soon come to dominate, though. Despite being instrumental, this song’s structure does an excellent job of conveying a dramatic story. There is a section led by piano and clarinet that sounds particularly ahead-of-its-time. “Sckxyss” flows right out of “Sohïa” and continues with the tight, tense jazz-rock. This is the shortest song on the album and features some powerful bass playing.

Disc one ends on “Auraë”. It’s a piano-focused piece and heavily features strange, dissonant intervals. Though some passages here are emblematic of Magma’s more iconic sound, many passages are more akin to the jazzier Canterbury acts, like Soft Machine.

Disc two of Magma is about a traveler from Earth asking the Kobaïans to return to Earth to teach the people how to live peacefully.

“Thaud Zaïa” opens with a lone, haunting flute before the appearance of a somber piano, restrained percussion, and plaintive vocals. The saxophone unfortunately does not quite fit in this first part, and this song takes a bit too long to get going. A looming, proto-metallic guitar riff swoops in, against which the sharp saxes clash wonderfully. Despite some decent ideas, though, this is one of the weaker songs on the album, as it feels somewhat aimless.

Next is the longest song on the album, the 13-minute “Naü Extila”. Written by bassist Laurent Thibault, the generous folk inclusions bear resemblance to his eventual solo album (Mais on ne peut pas rêver tout le temps, a fantastic hidden gem). After the quiet intro, it launches into a section of groovy blues rock before veering off into Van der Graaf-y percussion and saxophone. Though a bit disjointed, this song features some of the best music on Magma, and its prominent use of acoustic guitar makes it unique in Magma’s oeuvre.

“Stöah” opens with shrill screeching and ugly brass, and is one of my least favorite songs on the album. Despite this unpleasantness, it shows most clearly Magma’s eventual direction in its second half. The album ends with “Mûh”. Some of the brass passages on here remind me of Hot Rats or other early Zappa recordings. “Mûh” is a good overall song, but by this point, the sheer length of Magma is working against it. The album is too long, and it’s evident that some songs here were just slapped together.

Especially in Magma’s early days, the band would often record studio material and then perfect it on the road after the fact. As such, many of these early recordings have superior live renditions.

After the release of Magma, bassist Laurent Thibault would leave the band, as well as guitarist/flautist Claude Engel. The band would replace Thibault with Francis Moze, but Magma would continue on guitarless for their next album.

1001° Centigrades, also called 2, was released about a year after Magma. By ditching the guitar, Magma continued to refine their sound and move away from traditional rock structures. This album is still not quite 100% zeuhl, but it’s getting there. The jazz influences on 1001° Centigrades remain obvious and salient among the rock elements.

This album’s story starts with the Kobaïans arriving on Earth to tell their story. The Earthlings are seemingly receptive, but their leaders imprison the Kobaïans and impound their spaceship.The Kobaïans back on Kobaïa give Earth an ultimatum to release the prisoners, or else they will unleash their ultimate weapon and destroy Earth. The Earthlings agree, and the Kobaïans are released, but stories about them continue to circulate on Earth.

1001° Centigrades opens with the side-long epic “Rïah Sahïltaahk”. Bouncy piano and warm clarinet push it along, and this opening passage is some of the most accessible music Magma has ever recorded. (Check out this live rendition, where it was reworked to prominently feature guitar. It’s vastly different from the studio version, and superior, I would argue.) After this energetic opening, the song enters a slower, more plodding movement, though that soon transitions to something lighter and jazzy.

The Zappa comparison I made for Magma is every bit as apt here. It’s weird, jazz-filled, and technical, though it lacks any of Zappa’s guitar theatrics or overt humor.

“Rïah Sahïltaahk” is an impressive composition, but it suffers from some of the structural ills of songs on Magma. At times, it feels disjointed, and for all its strong moments, it lacks cohesion.

Side two features just two long songs. The first is “‘Iss’ Lanseï Doïa”, and it’s one of my least-favorite songs in Magma’s catalog. The first third is an odd, slinking jazz piece that sounds more like something I would hear from Charles Mingus than Magma. The second third feels more like Magma however, and I like a lot of the warmer moments, though it is admittedly inconsistent. The last third of the piece is a return to the structure of the first third.

The album ends on “Ki Ïahl Ö Lïahk”. After opening with a strange, ascending bassline, circling reed passages, and sharp piano, it develops an insistent marching beat. The song’s midsection interpolates between straightforward jazz fusion, à la Return to Forever, and Magma’s typical strangeness.

After the release of 1001° Centigrades, there was internal disagreement about the band’s direction. Christian Vander and others wanted to keep evolving the sound into something more celestial, whereas others wanted to keep the group in a jazzy vein. Two members (a saxophonist and their keyboardist) would split off to form the band Zao, which continued on in this style.

In 1972, Magma released an album under the pseudonym Univeria Zekt. This album, The Unnamables, was meant to be something of an introduction to the sound of Magma. The Unnamables completely ditches all the sci-fi themes of their first two albums, and the lyrics are sung in English on side one.

There are similarities to Magma’s sound on side one, especially to their self-titled release. It heavily features groovy, jazzy blues rock with exciting and unconventional structures. The song “Altcheringa” sounds like The Rolling Stones and Santana collaborated to try to record a zeuhl song. “Clementine”, meanwhile, is a gentle bit of prog-folk. Side one closes on “Something’s Cast a Spell”, an energetic, bluesy cut that reminds me of the underground hard rock act The Gun. The brass arrangement features Magma’s signature oddness, though.

Side two contains Christian Vander’s three contributions to The Unnamables. The first is “Ourania”, and it’s immediately obvious that side one had been written by the other band members. The flow is smooth and relaxed, with piano and gentle brass leading the way. Vander’s drumming is the real star here though, especially in the song’s second half.

Following is the 11-minute “Africa Anteria”, which opens with a bouncy jazz-rock passage that goes through some fun evolutions. The squealing saxophones in the foreground grow grating after a few repetitions, but they don’t stick around for that long.

The Unnamables closes on “Undia”, the most Magma-like song on the album. After starting as a gentle acoustic piece, growling organ and brash brass enter to add some propulsion to the piece. The lyrics are in Kobaïan, as well, though this is outside of the Kobaïa mythos, as far as I know.

Mëkanïk II: Expanding the Kobaïa Mythos (1973-1977)

It’s at this point that the chronology of the Kobaïa mythos gets weird. The first two albums are the fourth and fifth in the overall arc, respectively. Following the events of 1001° Centigrades, there is a trilogy of albums referred to as the Theusz Hamtaahk (“Time of Hatred”) trilogy. Within this trilogy, Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh (MDK, for short), Magma’s next album, is the third movement. Ẁurdah Ïtah, the second movement, was released subsequently in 1974, and Theusz Hamtaahk, despite being a fixture of Magma’s live shows, has never been recorded in the studio.

Before recording MDK, Magma underwent yet another significant line-up change. Bassist Jannick Top joined the band and would stay with Magma for a few albums; guitar was once more added to the line-up; and, perhaps most significantly, Christian Vander’s wife, Stella Vander, joined as a vocalist. Stella Vander has remained a consistent member of Magma since joining, and her vocals are a key component of their sound.

Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh (“Movement (of the) Destroying Commando Force”), Magma’s 1973 album, is also their best-known release. It tells the story of Nëbëhr Gudahtt, a follower of Köhntarkösz (more on him/that album later) who convinces the Earthlings to finally give up their warlike ways and live in peaceful enlightenment. His message is rejected at first, but one by one, the Earthlings are swayed to his message.

MDK opens with “Hortz Fur Dëhn Štekëhn Ẁešt”, and it is at this point where Magma truly invented zeuhl. There’s an insistent, marching rhythm being pounded out by piano, topped with Kobaïan chanting. It’s hypnotic and slow-building, and when the brass enters at around two minutes, the sense of doom is palpable. A small choir of female vocalists enters, adding soprano contrast to Klaus Blasquiz’s lower intonations.

Throughout “Hortz Fur Dëhn Štekëhn Ẁešt”, the interplay between the vocalists is strong, and though guitar is far from the lead instrument, its reintroduction is much appreciated. There’s a powerful, militaristic quality to this song, and that atmosphere would go on to become one of Magma’s signature elements.

Next comes “Ïma Sürï Dondaï”, which opens with light, jazzy piano and vocals, but this quickly interpolates with big, impactful blasts of brass and the choir. Instrumentally, Vander’s drumming is the real highlight here (as it is elsewhere on the album). Despite only being a little over four minutes, this song moves cohesively through a surprising amount of musical territory.

“Kobaïa Iss Dëh Hündïn” follows in the track list. It opens with foreboding guitars and piano, and continues MDK’s strong forward momentum. The tinkling piano and chimes, coupled with the otherworldly vocals and dramatic horns, is one of the best examples of the prototypical zeuhl sound.

Side two of MDK opens with “Da Zeuhl Ẁortz Mëkanïk”. Much like side one, the immediate impact is a doom-filled march. The atmosphere is oppressive, but it quickly gives way to something a little lighter. As much as I like the individual elements of this song, this is the one point on the album where things feel a bit drawn-out. There is plenty going on, and I understand that repetition is a key element of Magma’s sound, but it doesn’t quite 100% work for me here.

“Nëbëhr Gudahtt” has a gentle opening of insistent piano and some light bass work. Kobaïan vocals slowly enter, alongside spectral organ tones. The intensity gradually increases until it reaches a frenzied state by the song’s midpoint.

“Mëkanïk Kömmandöh” features a bit of funk in the bassline, and the horns are especially jazzy. The organ has a lovely, swirling texture, and the near-ritualistic nature of the music is clearly conveyed in the repetition. The closing “Kreühn Köhrmahn Ïss Dëh Hündin” is much slower and more hymn-like than the preceding experimental space-jazz fury, though it does eventually build to a powerful climax.

Magma’s next album has the most interesting backstory of any of their releases. Released in mid-1974, Ẁurdah Ïtah (Kobaïan for “Dead Earth”) is the second movement of the Theusz Hamtaahk trilogy and a prequel to MDK. As mentioned above, the eponymous Theusz Hamtaahk is the first movement, but it has never been recorded in the studio. The available summaries of the stories within these first two movements are vague. Theusz Hamtaahk tells the story of a terribly destructive war, and Ẁurdah Ïtah is about its aftermath.

Ẁurdah Ïtah, though, was not initially released under that name. That didn’t happen until its reissue in 1989. In 1974, it was released as Tristan et Iseult, a Christian Vander solo album and soundtrack to a film of the same name.

In 1972, Magma recorded some demo tapes. Filmmaker Yvan Lagrange got a hold of them and used them (without permission) for his avant-garde film Tristan et Iseult, a non-traditional retelling of the chivalric story of the same name. The film is incredibly hard to get a hold of, and the only people who seem to know about it are Magma fans and diehard experimental cinephiles. Based on reviews on Letterboxd, the film is confusing and involves a lot of horses.

Somehow, Christian Vander found out about this small-budget, unsuccessful film and got Lagrange to agree to fund a proper soundtrack in exchange for not being sued.

The result is the most stripped-down release in Magma’s discography. Featuring just drums, bass, piano, and vocals, Ẁurdah Ïtah stands in stark contrast to its lush predecessors. Fittingly for an album titled “Dead Earth,” such spartanness might have been a smart stylistic choice. (Though I do get the sense that Lagrange couldn’t exactly fund an enormous production.)

Due to its limited sound palette, conception as one unified composition, and emphasis on repetition and gradual change, Ẁurdah Ïtah is difficult to analyze on a track-by-track basis. It is best enjoyed as one massive suite.

“Malaẁëlëkaahm” opens the album on a rapid chant before dissolving into something moodier and more atmospheric. As with MDK before it, Ẁurdah Ïtah is quick to establish a ritualistic mood. Jazz elements are more obvious here, and the album feels more grounded overall, perhaps due to the sparse instrumentation.

“Bradïa Da Zïmehn Iëgah” is a brief, woozy, wobbly piece where ostinato piano and shuffling drums provide backing for Kobaïan vocals. “Manëh Fur Da Zëss” continues in this vein for another short song.

“Fur Dï hël Kobaïa” is a bit slow to get going, but it eventually turns into a driving piece where the many layers of overdubbed vocals work together wonderfully. The structure is constantly changing, but it somehow managed to feel like it all belongs together. “Blüm Tendiwa” is another gradual build from a quiet intro, but this piece is the most cosmic-sounding yet.

The first half of this record ends on “Ẁohldünt Mᴧëm Dëẁëlëss”. It has a bouncy, ascending melody, and Stella Vander’s vocals are the real star of this song.

“Ẁaïnsaht !!!” opens with some weird, processed vocals and one repeated piano note, but it soon returns to the sound that has dominated the album up to this point. “Ẁlasïk Steuhn Kobaïa” is an exciting track where emphasis is placed on the piano and bass, as opposed to vocals and drums.

“Sëhnntëht Dros Ẁurdah Süms” keeps the energy up and plays around with dynamics. Electric piano is also deployed here, and even that slight change in sound adds a lot. The opening chant from “Malaẁëlëkaahm” is revisited in a sunnier rendition (itself evocative of the opening of Theusz Hamtaahk), and more themes are revisited in “C’est la vie qui les a menés là !”. The second half of this song again shifts the focus to the piano, and the result is strongly reminiscent of Van der Graaf Generator’s best work.

Ẁurdah Ïtah closes on “De Zeuhl Ündazïr”, a song which foreshadows musical themes from Mekanïk Destruktïẁ Kommandöh, emphasizing the connection between these two albums.

I really don’t know why Magma haven’t recorded Theusz Hamtaahk in the studio yet. Live renditions are available on YouTube though, and it’s one of their best compositions.

Magma’s next album would be the first in a new trilogy of albums, the Köhntarkösz trilogy. This trilogy is the earliest part of the Kobaïa mythos, preceding the events of Magma’s self-titled. Released only three months after Ẁurdah Ïtah, 1974’s Köhntarkösz is the second entry in this trilogy, though its two companion pieces would not be recorded until the 21st century.

Köhntarkösz tells the story of an Earthling named Köhntarkösz. The story is, again, a bit unclear, but Köhntarkösz seems to have been an archaeologist or explorer. He discovers the tomb of an Egyptian king (Ëmëhntëht-Rê). Köhntarkösz gets a vision of Ëmëhntëht-Rê while in the tomb and is given insight into the evils of humanity. He also receives a vision of how to save humanity (efforts later undertaken by Nëbëhr Gudahtt on MDK), and there is a prophecy that Earth will be attacked by an enemy called Ork.

The centerpiece of Köhntarkösz is its 30-minute title track, which opens with creepy synthesizers and tumbling drums before launching into some slowly-chanted vocals. Compared to the frenetic, scaled-back Ẁurdah Ïtah, Köhntarkösz’s lush atmosphere and deliberate pace help establish it as something unique from the Theusz Hamtaahk trilogy.

The music on Köhntarkösz has an abstract, spiritual feeling to it. It’s a completely different vibe from what preceded this record, but it’s still unmistakably Magma.

The second half of “Köhntarkösz” sees the band launch into something more energetic and aggressive, and some of the organ tones are evocative of early Pink Floyd. The extended solo is some of the flashiest instrumentalism you’ll find on any of Magma’s studio releases.

Köhntarkösz also features two shorter songs. The first of these is “Ork Alarm”, a foreboding song full of looming strings and synths. It certainly lends the impression of a vision of a future war with an alien enemy. The other short song is “Coltrane Sundia”, an elegy for John Coltrane wholly unrelated to Magma’s mythology.

It was around this time in the band’s history that Mexican filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowski approached Christian Vander about having Magma provide music for his abortive film adaptation of Dune. (I also referenced this in my Pink Floyd Deep Dive.) Magma would have scored scenes with the Harkonnens, and Magma’s harsh, militaristic style would have suited it perfectly. Alas, Jodorowski’s vision for Dune was 14 hours long, immensely expensive, and reliant upon visual effects which hadn’t been invented yet.

After Köhntarkösz, Magma experienced another significant lineup change. Bassist Jannick Top left over fraying relations with Christian Vander, and violinist Didier Lockwood joined the group. Magma released their acclaimed live album Hhaï, which I quite hhaï-ly recommend. Lockwood would not stay on for any studio releases, but Top briefly rejoined the band for their next album.

Mëkanïk III: Changing Sounds and Hiatus (1976-1984)

After Köhntarkösz, the Kobaïa storyline becomes even more vague. Even people who have spent a lot more time poring over Magma’s lyrics than I have don’t seem to have much in the way of specific plot points for Magma’s next two albums: Üdü Ẁüdü (1976) and Attahk (1978). The best synopsis I’ve been able to find is that they’re both about the war between Earth and Ork, and their placement within the Kobaïa mythos is unclear. They follow the Theusz Hamtaahk trilogy, but which of the two comes first is not evident.

Üdü Ẁüdü marks a shift in Magma’s sound. It’s more accessible, more synth-heavy, and features prominent jazz and funk inclusions. Much of this can be attributed to the increased input from bassist Jannick Top in the songwriting.

Üdü Ẁüdü’s title track kicks things off on a peppy note. There’s a certain tropical characteristic to this song, and it’s almost like Magma is playing calypso. There’s still that signature ethereal quality to it, and Top’s bass work is especially impressive.

“Weidorje” follows and is more typical of Magma’s style. The focus is on a hypnotic groove, and the bass has a warm, fuzzy growl to it. This song features Bernard Paganotti on bass and co-lead vocals. Of note, he and Magma keyboardist Patrick Gauthier would leave the band to form their own zeuhl act, also called Weidorje, after this album. Weidorje’s sole album, a self-titled release in 1978, is fantastic.

Squeaky synths open up “Tröller Tanz (Troll’s Dance)” before moving into a passage that almost sounds like a Jethro Tull song, owing to the flute-like lead synthesizer. The piercing, panicky synths come back briefly, after which the song returns to Magma’s more typical fare. The pulsing throb of the bass and a reasonable runtime help keep this song surprisingly accessible.

“Soleil d’Ork (Ork’s Sun)” is the first of two compositions from bassist Jannick Top on Üdü Ẁüdü. Funk elements are immediately noticeable in the wah-wahed guitar and popped bass. This quality is counterbalanced by ritualistic chanting and chimes to give the impression of some strange alien rite. Something similar can be heard in the shorter songs of the band Om, particularly “Cremation Ghat I”.

Next comes “Zombies (Ghost Dance)”, a staple of Magma’s live shows. The bass groove is once again the focus of the song, with drum, vocal, and synth embellishments added on top to build tension.

Side two of Üdü Ẁüdü is wholly taken up by the massive “De Futura” (originally titled “De Futura Hiroshima”). This is the other Jannick Top composition on the album, and you can tell that a bassist wrote this song.

After opening with a stumbling, downward guitar line and electric piano accents, the song sets off on an indefatigable march. The rhythm section of Vander and Top push forward insistently, bringing the chanted vocals and eerie synth along with them.

Top’s bass snarls and commands the listener’s attention as a soundscape of war and despair swirls incessantly. Much of the last ten minutes of this song is a chance for Top to really flex his skills as a bassist. Paired with a drummer as skilled as Christian Vander, this rhythm section can play lead like few others. There’s a sense of anxiety in the extended jam, and synths and occasional vocals are deployed smartly.

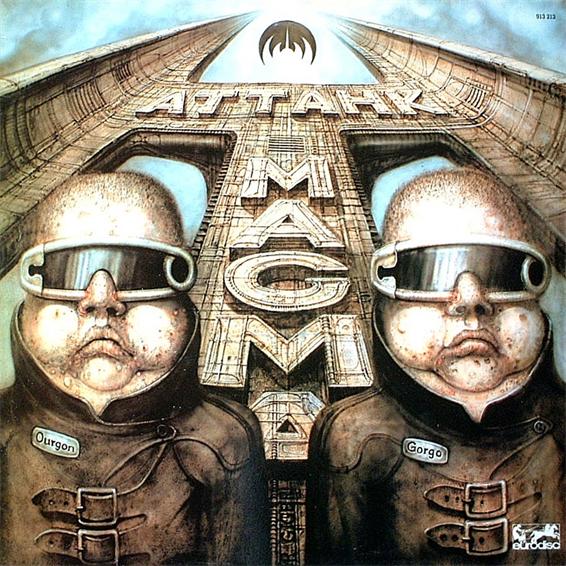

After Üdü Ẁüdü, Jannick Top would leave Magma to form the electronic band Space. Magma, in turn, would continue to tweak their sound. 1978’s Attahk, saw the band integrate more funk, soul, R&B, and gospel elements into their music. The album cover was designed by H.R. Giger, and some fans have speculated that the strange figures on it, Ürgon and Ğorğo, are from Ork.

“The Last Seven Minutes (1970-1971, Phase II)” is an energetic opener, featuring charging bass, keys, and drums. Around two minutes in, we get our first glimpse of Magma’s new, funkier sound in a section that could almost be described as proto-hip-hop. Funk elements are evident throughout the song’s core, though only Magma could have made a record that sounds quite like this one, while the closing section sounds like something off MDK.

What follows is “Spiritual (Negro Song)”, and the soul and gospel elements are unmistakable. (This song has been retitled to “Spiritual (Gospel)” on the most recent CD reissue.) Magma’s music always had a certain hymnal quality to it, and adding in the warm, uplifting tones of gospel music seems natural and intuitive. “Rindë (Eastern Song)” is another short song, though rather less jubilant than “Spiritual”. This piano-and-vocals piece sounds like a throwback to Ẁurdah Ïtah and is one of the weaker tracks on Attahk.

Side one ends with “Liriïk Necronomicus Kahnt (in which our heroes Ürgon & Ğorğo Meet)”, and some similarities with “The Last Seven Minutes” are immediately evident. It also kicks off with an energetic, bouncing instrumental passage featuring some lightly-distorted scat singing. Jumpy, fuzzy bass provides the primary backing for the vocals and retains significant momentum.

Sequenced synthesizers, brass, and crashing drums open up side two on “Maahnt (The Wizard’s Fight Versus the Devil)”. The verses are reminiscent of Üdü Ẁüdü with their minimal, bass-forward instrumentation. Distorted vocals and spooky synths effectively convey the feeling of battling the devil. Brass returns in the song’s second half as it builds toward a climactic synth solo.

After such a grandiose track, “Dondaï (To an Eternal Love)” effectively cools things off. It’s in the same vein as “Spiritual”: a mellow, warm, piano-based piece with a soulful backbone. Crunchy bass enters in the second half of the song, adding to its intensity.

Attahk ends on “Nono (1978, Phase II)”. “Nono” is a tense song. The opening bassline is inviting, but electric piano, skittering high-hats, and intense vocals propel it anxiously forward. The backing choir, though, eventually gives the song a hopeful, uplifting tone, perhaps signaling a sort of rebirth following the war with Ork.

Following the release of Attahk, Magma toured extensively for several years and put out the seminal live album Retrospektïẁ (Parts I+II) (featuring Theusz Hamtaahk for the first time) and the slightly-less-seminal-but-still-excellent Retrospektïẁ (Part III).

Magma’s next studio album would be 1984’s Merci. Merci is the one Magma album which does not touch on the Kobaïa mythos. All the songs are sung in French or English, and the band went in more of a jazz-funk direction.

Merci opens on “Call from the Dark (Ooh Ooh Baby)”, and it is so disorienting to hear Stella Vander use words I can actually understand. There’s a smooth, laid-back funkiness to this synth-fueled song, and the brass arrangement is genuinely pleasant. The English vocals are so different from what I expect of Magma though that it is distracting. The music itself is fine, if a bit undistinguished and long-winded.

Up next is the only song off this album which would remain in their live repertoire, “Otis”. It’s a relaxed piece, and I find the French lyrics less distracting. Some of the piano and vocal arrangements are evocative of past Magma songs, such as “Dondaï”. Near the song’s end, it picks up energy and has a fun synth solo. “Otis” isn’t a great song, but it’s enjoyable enough.

Next comes “Do the Music”, which is the most Magma-y song yet on the record. It features staccato brass and unorthodox vocal arrangements, and Christian Vander’s drumming is sharp. This song sounds like an outtake from Attahk and is the best cut so far. This piece is high-energy with a dose of Magma’s signature weirdness. After this track comes a brief epilog/reprise of “Otis”.

The opening brass arrangement of “I Must Run” sounds like a theme song from a 1980s sitcom, and the piano led-verses don’t do much to dispel that perception. This one isn’t very good.

The longest song on the album is “Eliphas Levi”. Distant, lilting flutes and light hand-drums open this track up on a gentle, jazzy note. It meanders for its 11-minute runtime without much development or evolution, unfortunately. It acts as pleasant-enough background music, but there is nothing here to hold one’s attention.

Merci ends on “The Night We Died”, an apt name for the last song on what the band thought would be its last album. Piano and vocals lead this song, and I am pretty confident that the vocals are in Kobaïan, though divorced from the mythology and structured more like scat-singing.

Magma disbanded not long after the release of Merci, and Christian Vander went on to play in a handful of jazz acts. In 1989, several Magma albums were reissued, including an archival version of MDK called Mekanïk Kommandöh. It’s more raw and stripped-down than the original, lacking any of the brass elements. It’s good, and some people prefer this version, but I don’t think you need both versions in your library.

Mëkanïk IV: Reunion and Continued Work (1996-Present)

Christian Vander was approached at least twice about re-forming Magma. The first time was in 1989, but that did not lead anywhere. Then, in 1996, he was approached about it again, though he was skeptical that anyone was still interested in the band. After the organizer quickly booked several gigs for Magma, Christian Vander hurriedly assembled a lineup from ex-members of his most recent band, Offering.

Eventually, Magma’s membership would somewhat solidify and become fairly stable. There was still some churn, but guitar, bass, keys, and (some) vocalists would be consistent. Despite divorcing from Christian at some point during the band’s hiatus, Stella Vander has remained a member of Magma since their reunion.

In 2004, Magma released their first album in two decades, Köhntarkösz Anteria, more commonly referred to as KA. The material on KA was mostly written around 1973-74, and pieces can be heard on the live album Inédits.

KA also sees a return to the Kobaïa mythos. This album acts as a prequel to 1974’s Köhntarkösz and is the first chronological entry in the Kobaïa storyline. The album covers Köhntarkösz’s youth, before he was awoken into his role as a prophet, and ends where Köhntarkösz begins: at the entrance of the tomb of Ëmëhntëhtt-Rê.

KA features three long songs, titled “K.A I-III”. Part I is an immediate return to form for Magma. Dense layers of vocals, unusual rhythms, and impactful bass and drums propel this piece along. It doesn’t take long for this composition to plunge headlong into Magma’s repetitive, ritualistic mood. In instrumental passages, the bass is the star of the show. Philippe Bussonnet would remain with Magma for over a decade, and his playing is one of the things which has made their post-reunion work so strong.

Part II continues in this general mold. The vocal arrangements are strongly reminiscent of church choirs with their uplifting tones, and the fluctuation between irregular, bouncing beats and smoother passages works wonderfully. Guitarist James Mac Gaw’s work is understated but integral to this new version of Magma. He adds to the richness of the sound without stealing the show.

In the song’s second half, Magma enters a gentler, quieter movement. The piece floats along in a relaxed state, and the minimalist arrangement lets the various elements stand on their own. The eventual return to more powerful passages is that much more impactful when contrasted against this lull.

“K.A III” is the best individual song Magma has ever recorded, and it is one of the crown jewels of progressive rock. It’s a combination of two older pieces, “Om Zanka” and “Gamma Anteria”, both of which appear on live recordings.

The “Om Zanka” portion of Part III opens with an emphatic chord, followed by a tense, palm-muted guitar line. A warm, serpentine synth line quietly wriggles into place, supported by electric piano and light percussion. There’s a rolling, meditative quality to this passage, including distant, moaned vocals. Once the vocals give way, an extended synth solo takes the lead. Vander’s percussion keeps building in intensity under the other band members’ relatively mellow parts. As the solo progresses, the vocals re-enter, more intense and frenzied than before.

The shift to the “Gamma Anteria” section is sudden but not jarring. Chanting vocals are again the focus over the tight, complex rhythms and riffs laid down by the instruments. Vander’s drumming pushes the band harder and harder throughout this massive track’s runtime; the steady pace and duration of the acceleration is impressive.

As the song enters its final five minutes, the song reaches new heights. Vander’s powerful drumming, the sublime vocal arrangements, and tight interplay between bass, guitar, and piano accelerate this song into ecstatic realms. The repeated chants of “Allëhlüïa!” emphasize the ritualistic, esoteric nature of the music. Bussonnet practically shreds his bass as the vocalists reach new heights of frenzy.

Magma’s next album, 2009’s Ëmëhntëhtt-Ré, consists of more music originally composed in the 1970s but never recorded in the studio. This is also the third installment of the Köhntarkösz trilogy, taking place after Köhntarkösz opened the tomb of Ëmëhntëhtt-Rê at the end of the 1974 album. (I know that “Rê” and “Ré” have different diacritics depending on whether it’s the album title or the character, but that’s just how it is. I wanted to clarify that this wasn’t an error on my part.)

Though Ëmëhntëhtt-Ré is the third part of the Köhntarkösz trilogy, it is mostly a flashback. This album tells the story of the pharaoh Ëmëhntëhtt-Rê, who had a vision for saving the world, but who was murdered before he could complete it. After Köhntarkösz opens the tomb, the pharaoh takes over his body and uses this new vessel to fulfill his prophetic vision.

The bulk of the album is four tracks titled “Ëmëhntëhtt-Ré I-IV”. Part I opens with ominous chanting and rumbling piano and drums. The music swirls and swells for a while, remaining impressionistic.

Part I flows smoothly into Part II with warm bass and piano lifting the music upward. Soul influences are evident in the first minute before plunging into a speedy, peppy section. Vibraphone adds a lightness to the astral prog-jazz. Part II incorporates elements of the song “Hhaï”, previously only heard in live settings. The vocal performance is especially impassioned. As this segment of Part II reaches its climax, James Mac Gaw’s guitar flourishes add wonderful flavor and depth to the experience.

With about eight minutes left, this movement enters a stretch of tension, with a high-strung bassline and nervous piano leading the way. The song becomes weird and dark, with sharp, distorted guitar lines harmonizing with piercing vocals.

Part III kicks off on a haunting choral arrangement, and those first ten seconds are some of the most striking music in Magma’s history. Past this impactful opening, Part III plays with subtlety. This movement is quiet for its first several minutes, and a sense of impending doom is effectively cultivated. Part IV, in contrast, is a softer, gentler experience.

“Funëhrarïum Kanht” is super creepy, and if you’re looking for music for your next haunted house, give this a go! Finally, “Sêhë” is a weird bit of breathy, dissonant keys and spoken Kobaïan.

Magma’s next release was 2012’s Félicité Thösz (“In Praise of Thösz”). Félicité Thösz featured the first new material written after Magma’s reunion, which Christian Vander wrote primarily in 2001 and 2002. Its placement in the Kobaïa mythos is not entirely clear, either.

This record is best thought of as the massive, 28-minute title track, plus the brief “Les Hommes Sont Venus”. The tone of this album is markedly different from most of Magma’s discography. Much of their output has been dark, militaristic, and imposing. Félicité Thösz is light, joyful, and hopeful; and its minimal instrumentation harkens back to Ẁurdah Ïtah. However, without the financial limitations of that album, Félicité Thösz is able to sound richer than Ẁurdah Ïtah.

“Ëkmah”, the opening movement, is one of the album’s darker passages. It’s a fittingly dramatic introduction, though even by the standards of this release, it’s a simple, spare piece of music. This somber tone stands in contrast to the hopeful warmth of “Ëlss”, where piano and guitar provide a reassuring backing to luxurious vocal arrangements.

“Dzoï” features some tense guitar passages, and the slinking quality of the music is superb. The five-minute “Tëha” is the longest subsection of this album. It’s uplifting and optimistic and full of multi-layered choral arrangements. Following this track is “Ẁaahrz”, a gorgeous, four-minute piano solo.

“Dühl” starts to build the tension back up, and “Tsaï !” is the darkest bit of music on the album. This passage would have fit in seamlessly on Ëmëhntëhtt-Ré with its driving rhythm and out-of-this-world bass work.

Opening with otherworldly chants, “Öhst” is the clear climax of the album. Christian Vander takes lead vocals on this track over a simple piano ostinato backing. As the song progresses, bass and simple percussion gradually build. Vander’s vocal style is distinctive, and it suits this musical passage perfectly. The percussion gradually becomes more complex, as do the backing vocals. The final 90 seconds is engrossing. For all the comparisons I’ve made to various religious rites, this bit feels the most like a genuine ritualistic celebration.

Félicité Thösz ends with “Les Hommes Sont Venus”, a hypnotic piece of vocals and chimes that was first performed in the early 1990s.

Magma’s next release was arguably their least-necessary. In honor of the band’s 45th anniversary, Christian Vander opted to re-record “Rïah Sahïltaahk” off 1001° Centigrades. It’s fine, I guess. The vocal performance is noticeably weaker, and the original’s brass passages have mostly been replaced with choral arrangements. There is guitar in this version, but you’ll be hard-pressed to pick it out. Nonetheless, it’s fine, just far from essential.

Coming a year later was the band’s next new release: the 21-minute Šlaǧ Tanƶ. Written sometime around 2009, this epic track is Magma’s heaviest release to date. Physical copies bear a sticker describing it as “jazz metal.” (I’ve run across it in record stores, but I just can’t mentally justify $30 for a 21-minute song.) Like Félicité Thösz, the placement of this song within the band’s broader mythology is not clear.

Starting with an off-kilter guitar riff, the song does not hesitate before getting to the aggression. The passage “Šlaǧ” is a pummeling piece of music. For the first time since their self-titled album, guitar is given the lead, and paired with Hervé Aknin’s dramatic vocals, this choice results in a sound which suits Magma fantastically. “Dümb” maintains continuity with the preceding passage, but it veers more explicitly into jazz territory with its bass noodling.

“Vers La Nuit” feels like a guitar-led passage off Félicité Thösz, and “Dümblaê (Le Silence Des Mondes)” is an effective bit of build-up. “Zü Zaïn !” revisits themes from earlier in the song and builds a sense of foreboding doom.

“Šlaǧ Tanƶ” sees piano, bass, and vocals vie for dominance as the song reaches its climax. Christian Vander, who had mostly yielded the spotlight prior to this point, finally starts showing off. The closing movement, “Wohldünt”, is somber and feels somewhat out-of-place with the preceding 19 minutes of fury.

Šlaǧ Tanƶ would be the last Magma release for pianist Jérémie Ternoy and guitarist James Mac Gaw. Mac Gaw sadly passed away from brain cancer in 2021, but he left an impressive legacy with Magma over the span of three albums, two EPs, and many, many live performances.

In addition to those personnel changes, 2019’s Zëss: Le Jour Du Néant features some other notable differences from past Magma releases. On it, Christian Vander provides lead vocals for the entire record, and Morgan Agren takes over for him on drums. The Prague Philharmonic Orchestra is utilized to add lushness and depth to the music. As I stated in my contemporaneous review of Zëss, symphonics mesh fantastically with Magma’s space-operatic style.

Zëss (Kobaïan for “master”) is, as far as I can tell, the conclusion of the Kobaïa storyline. Originally written in the late 1970s, it was often performed until the early 1980s, and it remained only partially finished for almost 40 years. I’ll let Christian Vander himself explain this album. In an interview with the German site Eclipsed, he said of Zëss’s story:

In the story that “Zëss” is about, at this moment a stage has been reached in which everyone has approximately the same level of understanding of the universe. For the finale, the masters have chosen a huge stadium somewhere in the universe, in which they stage a theatrical performance of the last day or night. The “master of language” who then speaks is at the same level of knowledge as the one who listens to him. It’s just a game, a theatrical idea.

Christian Vander

The lyrics are in both French and Kobaïan, and an English translation is provided in the CD booklet as well. So I should note that, if I really wanted to, I could use that like a Rosetta stone and flesh out the Kobaïan lexicon. That’s more work than I want to do, though, and I don’t speak French.

In revisiting Zëss for the first time in a while, I initially found I enjoyed it more than I originally recalled. It makes pretty good background music, but its repetitiveness and long-windedness make it sag under closer scrutiny. There’s a difference between the hypnotic, mantra-like grooves Magma is best known for and uncreative tedium. Zëss doesn’t quite reach depths to warrant such a description, but it’s not Magma’s most enthralling work.

Zëss opens with “Ẁöhm Dëhm Zeuhl Stadium (Hymne au Néant)”, an ominous, atmospheric piece. Wordless vocals, piano, and wavering strings build a sense of grandeur. Percussion and bass enter with “Da Zeuhl Ẁortz Dëhm Ẁrëhntt (Les Forces de l’Univers/Les Eléments)”. It’s a speedy, jazzy backdrop for Christian Vander’s dramatic spoken word.

The transition into “Dïwöóhr Spraser (La Voix qui Parle)” is smooth, but there’s little to differentiate it from the previous movement. There has been a gradual increase of intensity, but such tiny, incremental changes make this repetition a little tiring.

Strings and wind instruments grow in prominence in “Streüm Ündëts Ẁëhëm (Pont de l’En-Delá)”, but the repetitiveness of the backing track again continues to hold Zëss back from greatness. “Zëss Mahntëhr Kantöhm (Le Maître Chant)” features some change-ups; Stella Vander gets a chance in the spotlight, and the orchestral passages are quite nice.

“Zï Ïss Ẁöss Stëhëm (Vers l’Infiniment)” is the best passage on the album, owing largely to it switching up the formula of the other pieces. The backing chant of “Sanctus! Sanctus!” harkens back to Magma’s best ritualistic moments, and Christian Vander’s vocal performance is passionate. The last minute of this movement is a swirling flurry of strings and shrieks that creates a disorienting atmosphere. Zëss ends with “Dümgëhl Blaö (Glas Ultime)”, a slow and gentle outro.

Though the strings work very well, they feel over-relied-upon. There’s almost no textural variation, and this album could have benefitted from a bit of grit or contrast.

Right around the time I started writing this retrospective (early 2022), Magma announced they are getting ready to head back into the studio, so we’ll see what that produces. Maybe Theusz Hamtaahk will finally get recorded, or perhaps Vander has something else up his sleeve!

Edit: Read my review of their 2022 album, Kãrtëhl, here.

Mëkanïk V: TL;DR and Ranking

As I said at the beginning, Magma is both weird and pretty consistent in their quality. For the sake of clarifying the often muddled storyline of their music, here is (roughly) the order it takes place in. Note that The Unnamables (1972) and Merci (1984) are not related to this at all, and the placement of Félicité Thösz (2012) and Šlaǧ Tanƶ (2015) is not clear.

- Köhntarkösz trilogy

- Köhntarkösz Anteria (2004)

- Köhntarkösz (1974)

- Ëmëhntëhtt-Ré (2009)

- Magma (1970)

- 1001° Centigrades (1971)

- Theusz Hamtaahk trilogy

- Theusz Hamtaahk (n/a)

- Ẁurdah Ïtah (1974)

- Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh (1973)

- Üdü Ẁüdü (1976)

- Attahk (1978)

- Zëss (2019)

And here is how I would rank the quality of the albums (excluding Theusz Hamtaahk, since that has not had a studio release):

- Köhntarkösz Anteria (2004) (100/100)

- Ëmëhntëhtt-Ré (2009) (96/100)

- Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh (1973) (94/100)

- Félicité Thösz (2012) (90/100)

- Üdü Ẁüdü (1976) (90/100)

- Attahk (1978) (86/100)

- Šlaǧ Tanƶ (2015) (85/100)

- Ẁurdah Ïtah (1974) (83/100)

- Köhntarkösz (1974) (82/100)

- Magma (1970) (75/100)

- Zëss (2019) (74/100)

- The Unnamables (Univeria Zekt) (1972) (71/100)

- 1001° Centigrades (1971) (70/100)

- Rïah Sahïltaahk (2014) (60/100)

- Merci (1984) (53/100)

Thanks for a fascinating article – been meaning to properly explore Magma for a while. This’ll be a big help.

LikeLike

Thanks for this! You may enjoy my own take on the band: https://www.seaoftranquility.org/sections.php?op=viewarticle&artid=281

LikeLike

On an off chance you ever get back to this sort of thing, which of their live albums do you consider essential? They have…more than a few! Intimidating to dig through.

LikeLike

Hhaï is absolutely fantastic. It’s their best-rated release on RYM. Retrospektïẁ I-III is also great and features the seminal “Theusz Hamtaahk”. I’m then most familiar with their enormous live box set Kohnzert Zünd, so I have a hard time speaking to specific albums. That said, in that box set (which includes Hhaï) has some great renditions of “Riah Sahiltaahk” and “Emehntett-Rê”

LikeLike

Live Hhai is absolutely where to start. Kohntarkosz is one of the greatest compositions ever written.

LikeLike